Searching for traces — from the Kalchofengut to the Muckklause

During a visit to the Kalchofengut museum in Unken, I discover a long wooden bar with an iron hook at the end. I ask curator Sepp Auer what these bars are all about, and he begins to tell me the history of the wood workers in Salzburg’s Saalachtal valley. Due to the oldest still valid European treaty, the Bavarian-Austrian Salt Treaty of 1829, Bavaria owns around 18,000 hectares of forest on Austrian state territory. The wood was transported across mountain streams via the drift (in German “Trift”), using the water course of the Saalach river to Bavaria. The “Trifters” were those men who directed the wood with their long bars and moved it ahead.

It’s still morning on a wonderful summer day. So, I spontaneously decide to search for the traces of Unken’s Trifters at the Muckklause. With my mountain bike, I ride into the picturesque Heutal valley. Admiring the forests all around, I remember Sepp Auer’s words: “The forests around Unken provided wood for salt extraction in the salt works at Bad Reichenhall for hundreds of years. Lumberjacks and young men from the farms would cut down large areas of forest during the winter which were owned by the Bavarians. The cabinet saw was their tool of choice, which they would use from tree to tree to topple them. With heavily loaded sleds, they would ride through the depths of the forests with the logs all the way to the Muckklause.” Not much is left from the days of deforestation and I enjoy the shady trees along my route.

© Dorfarchiv Unken – During winter, the wood was transported to the Klause via wooden sleds

I cycle through the timber forest and make my way slightly downhill to the Kreuzbrücke bridge. Here, I fork off and a gorgeous forest path leads to the Winkloosalm mountain pasture. Approximately 100 metres after Tanzager, I park my bicycle and make my way down to the former Muckklause driftwood facility by foot. I enjoy the silence among the trees here, that is only interrupted by the monotonous splashing of the stream. The Muckklause, renovated in 1975, is an imposing construction of stone and wood and I recall Sepp Auer’s words again: “At the appropriate little streams, the water was dammed with the help of rock blocks and passage gates. This was also the case at the Muckklause at the confluence to the Mösererbach stream in Unken. In 1626, the structure was mentioned officially for the first time. The wood, which was brought to the Klause with sleds or across specifically built wood paths during winter then came for additional processing here. One unit of timber was approximately 90 cm long and was sharpened on the front and back.” Sepp Auer didn’t hesitate to explain why the timber needed to be sharpened like that, “Sharpening the timber prevented the wood from getting stuck in the water and made transportation easier.”

Fighting off the Fox

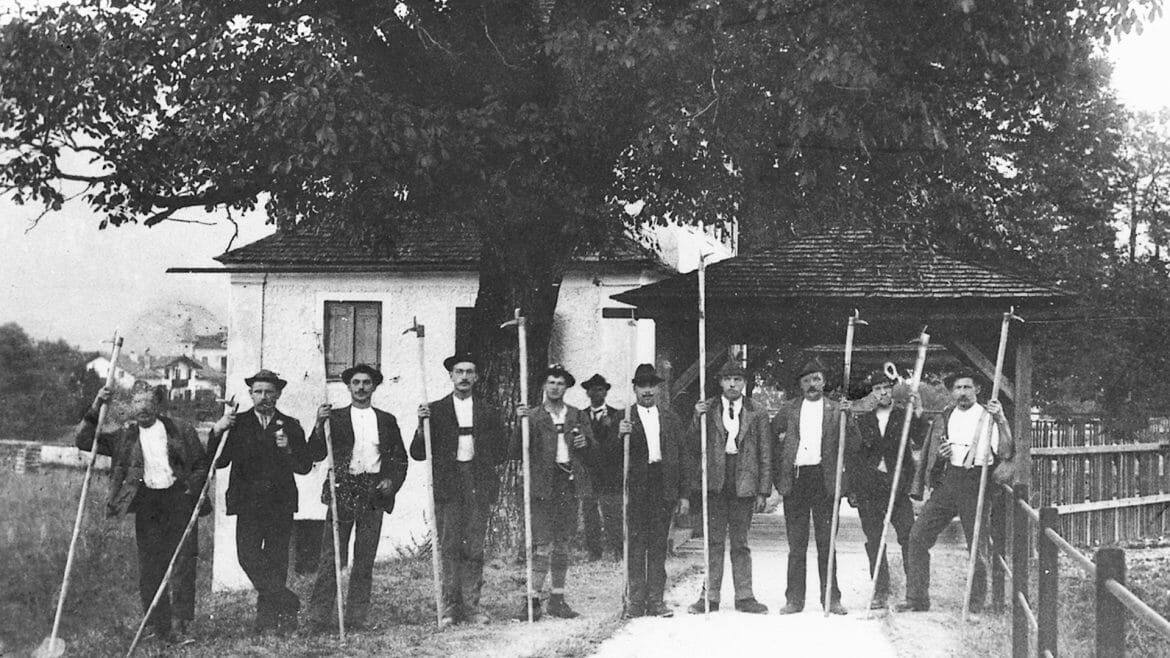

The sharpened pieces of wood were thrown into the stream bed in front of the Klause. As soon as all the wood was collected, the melting of the snow in the spring marked the beginning of the dangerous “Trift”. Trifting is the transportation of the wood through the course of the stream, for which around 14,000 cubic metres of water were dammed in the so-called “Klaushöfen”. “The Klause was then broken,” says Sepp Auer during our talk in Kalchofengut. “The gate of the Klause, made of wooden beams, was knocked down, which lead to the release of the dammed water with enormous force, dragging along all the accumulated wood. Even at tributary streams along the main stream, additional pockets were opened in order to complete the water flow. Then, the Trifters made sure that there wouldn’t be any pile ups. Such an obstruction was called a “Fuchs” (fox) and the risky unravelling of the entangled wood beams has cost many Trifters their lives.” With the long trifting bars, which were equipped with pointy hooks, the brave men fought off the Fuchs. On small rises, as can still be seen today in the Seisenbergklamm ravine, they pierced into and poked around the wood above the gushing water. One wrong step, a small slip, and they’d fall into the icy, raging whitewater. Or they would have to step into the water up to their bellies in order to move the wood in the right direction. The enormous risk was also the reason why only unmarried young men were allowed to work as Trifters. And many signs in Unken still remind of the countless lethal accidents that occurred during the practice. Miraculously survived accidents are documented in the Maria Kirchental pilgrimage church on the votive tablets.

© Dorfarchiv Unken – The brave Trifters with their long trifting poles

Coal comes in, trifting goes out

Once the tight Klausbach stream was overcome, the wood made its way into the Saalach river. Calmly and forcefully, the water took the wood all the way to the facilities in Reichenhall. “There was always a bit of loss, because not all the wood that was thrown into the water in Unken actually made it to Reichenhall. One part got stuck on the banks or was pulled ashore by the “Holzfischers” (wood fishermen). The Holzfischers were residents around the Saalach river that had a permit to collect a certain amount of wood for their own use. The salt works accepted this loss, because the Holzfischers prevented the wood from getting mixed up together and because there simply wasn’t another route to transport the wood. The Muckklause was used for trifting until 1911. When the salt works began using coal for their operations, it marked the end of the trifting practice.

The gentle swooshing of the stream amid the green forest pulls me back into the present — I look at the historic construction of the Muckklause one last time and hike back to the spot where I had left my mountain bike. On my way back to Kalchofengut, I can’t stop thinking about the adventurous story of Unken’s Trifters around the whitewater of Salzburg’s Saalachtal.